1 Timothy 1:12-17; Luke 15:1-10

So a sport that I’ve recently picked up is Sanda- Chinese kickboxing. If you’re not familiar with martial arts, it’s a full contact martial art that lets us use our hands, our legs, grappling, and to use throws.

My background is in fencing- I did it for a while and hope to get back into it once my gear fits again, and as a child and teenager I did some Karate, so the punching, kicking, and the footwork is familiar to me- this doesn’t mean I’m good at it, but it is familiar. What is new is the takedowns and the throws. If you’ve never had the experience of throwing someone or being thrown, oh boy, it’s wild. Throwing and being thrown is very different from the way we normally encounter the world. There are a lot of choices to be made when throwing someone, and some of those choices have some particularly nasty consequences. But there’s also things that you can do, especially when training or sparring, to make the fall easier and safer.

I will note for safety’s sake, kids, don’t try this at home, and no we did not go straight into this- we trained extensively on how to fall and how to roll- no i’m not going to do one right now, but trust me, I can. Key tips for everyone is to tuck your chin, don’t try to break your fall with outstretched arms, and engage your core muscles, and try not to let your head hit the ground.

I say this because a couple of weeks ago we had an exercise where everyone had to throw everyone else in the class. I was waiting in line when one of my fellow students was in the process of being thrown over someone’s shoulder and for a split second, he was on his back, parallel to the ground over this other guy’s shoulder. His eyes got wide for a second and he made a short gasp sound. The throw ended a split second later and he fell safely. Afterwards I went up to him and joked, “Nick, it looks like you saw God there for a second.” He replied, “Just wait until it’s your turn.”

And so I did. I think I understood; when you’re in the process of being thrown, there is very little you can do to change where you are. Of course, you can do work before it to not get thrown, and you can recover in different ways, including falling properly or rolling correctly, but in that moment, that split second, you are, at the mercy of your thrower. In a violent situation this can get very bad very quickly. It’s why the best means of self-defense is often to run away. Seriously.

Yet, thankfully, the folks in my class have a good rapport, and we work to not injure each other while training. Even if as a beginner I screw something up, my classmates won’t take it out on me. This is a profoundly Christian message.

So much of what we are called to do and show as Christians- forgiveness, grace, and yes, mercy, are a reflection of what God has already done for us. They are a recognition of our own powerlessness in the face of forces beyond our control; cosmic ones, yes, but also social ones, such as ignorance. In addition, I believe this is a calling for us to end cycles of retribution, violence, and exclusion as we can, following the example of Jesus. We are called to gather each other in, not drive each other out.

This is what drives the heart of our first reading. This letter, known as First Timothy, was traditionally understood to be a letter from the apostle Paul to Timothy giving some advice. Now we believe that this letter was probably not written by Paul, for many of the same reasons we don’t believe that Hebrews was not- the language used in this letter is different, than a letter like Galatians, Romans, or first Corinthians, and the church situations described in it are not the ones that Paul would have known of.

Instead scholars now believe it was someone else who wrote this letter- who we don’t know- probably around the year 150, although possibly as early as the year 100. They aren’t the theological masterworks of some of the other letters of the New Testament, and as letters of specific advice, this letter contains some things that are quite useful and some that aren’t.

Our section today is one of the nicer parts. It contains a phrase that is sometimes used as part of church services- I believe we have used it in our assurance of pardons after our prayer of confession on Communion Sunday- “The saying is sure and worthy of full acceptance: that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners”

It also contains the phrase that you might recognize from the hymn “Immortal, Invisible”.

But the main thrust of this passage is not literary references, but mercy. That is, our author did not receive the punishment that perhaps he “should” have. As someone who was, in his words “a blasphemer, a persecutor, and a man of violence”, he was not condemned by God or the fledgling Christian community, but rather, after he had turned away from his violence, accepted and eventually became a leader in it.

The story from Acts about Paul’s conversion, tells us that after Paul was knocked down from the heavenly light, he was blinded for a number of days, and left completely in the care of Damascus’ Christian community. Paul, once powerful, was rendered powerless. Yes, Paul had that same moment of helplessness that I had in the middle of being thrown. Yet his landing was made gentle. The community did not exact the justice that was rightly theirs to seek. They showed mercy instead.

Mercy happens when we pull back from retaliation, when we recognize that cycles of violence and exclusion do little more in the end then have us commit more violence and exclude more people. Just as God gathers us in, we are called to call each other into community, not call each other out, forcing each other out of community.

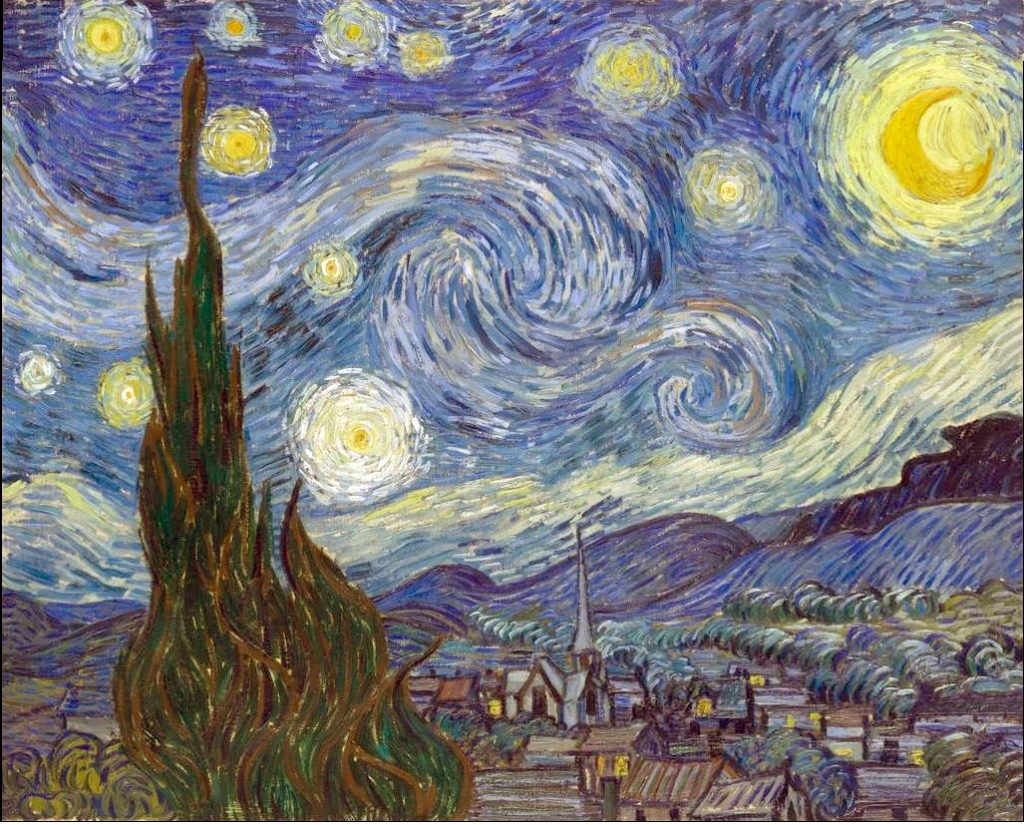

Perhaps Jesus’ parables are, for once, more straightforward. Jesus tells two stories in our Gospel reading; the first is a famous one for liberal and progressive Christians. Jesus tells the story of a sheep who wanders away. Instead of ignoring the sheep, shunning the sheep or even in more drastic terms, killing the sheep, Jesus goes to find the sheep, and return them to the flock.

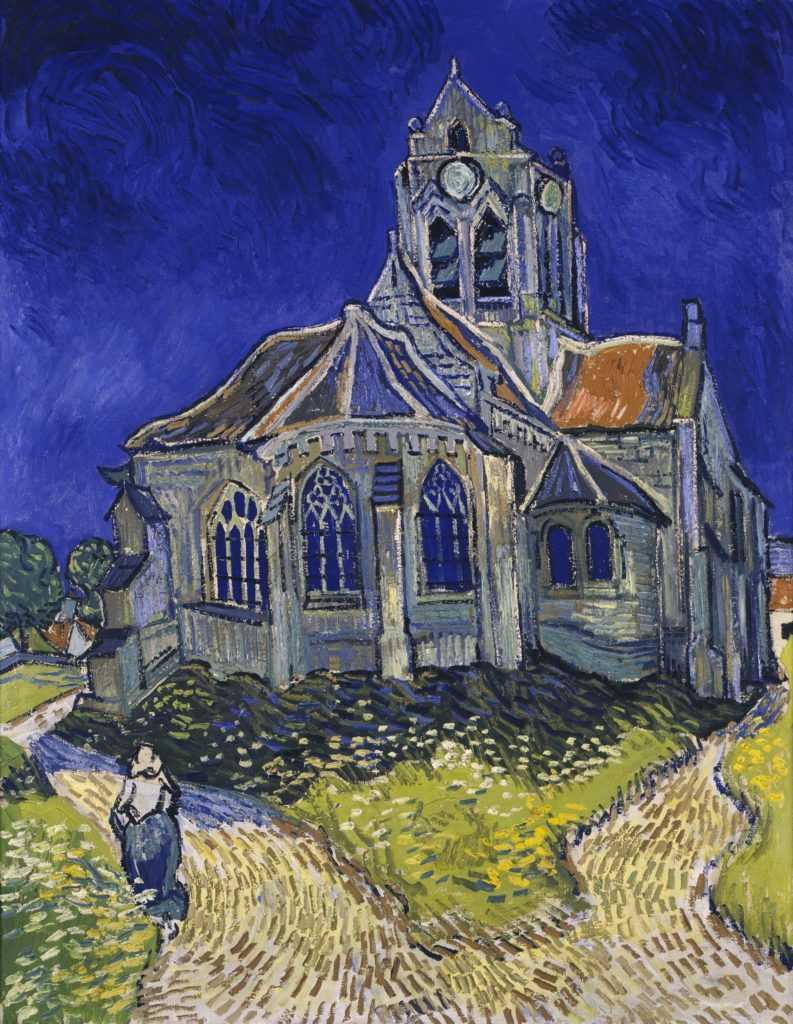

Different commenters from different cultures have had much to say about this story. Some have noted the joy of the sheep at being saved. Others have focused on the joy of the community and the flock at being made whole. Today, going with the theme of being picked up, I relish the imagery of the sheep being carried on the shoulders of their shepherd. The sheep is totally helpless, yet trusts in the shepherd’s abundant mercy to not harm it. Instead of punishment for the sheep, the shepherd seeks only reconciliation and healing.

Let us go and do likewise.

As we begin our moment of silent prayer and reflection, let us consider the many ways we have been shown mercy, and how we might show it to others. Amen.