Proverbs 8:1-4, 22-31; Psalm 8

Has anyone ever taken a job that seemed like a good idea at the time but ended up being a bad fit? For me it was my attempt as a car salesman in the summer of 2009. The recession was in full swing and it was right before cash for clunkers, so no one was buying. All the love in the world to natural salespeople, but I am not one of you. I lasted a full week.

For Vincent van Gogh, that failed career path was the professional ministry. At the age of 23, he was living in England after having been fired from teaching at a boarding house, and became a minister’s assistant at a Methodist church. This lasted about six months before he went home to the Netherlands, where he tried to study for the entrance exams to become a minister. He failed them miserably.

Then he tried to become a missionary; he chose not to go to far off lands, but to a small town in Belgium, where coal miners and their families lived savagely hard lives; many of the men who worked the mines did so from sun up to sun down, and rarely or never saw the sun. Pay was low, and families suffered from lung illnesses from coal dust and other pollutants.

Van Gogh knew that platitudes would do little for these people. He decided to get to know them, not from a distance, but in the same conditions as they did. The conservative church authorities thought that this “undermined the office” of pastor and removed him from his post.

Three times tried, and three times failed as a minister, yet it was these experiences that set him on his way to his artistic career.

But I do not wish to give a van Gogh lecture; there are artists and art historians who have dedicated their entire lives to his work and the meaning of it. Rather, what I hope is that we might examine together his art and philosophy in conjunction with our Bible readings and come to new understandings that might help us in our own religious understanding.

I think Van Gogh was a man who has much to contribute to our understandings. Although he was considered weird in his day, today we might call him a progressive Christian; I personally think he would fit in well at this church.

Three things lead me to that conclusion. First; he had a life-long love and devotion for nature and the rhythms of life that was spiritual in its nature. Second, he was willing to see God in places that many of his contemporaries did not; in nature, in novels, in other religions, and in the daily lives of ordinary people, not just saints. Third, he and related to this; he had a deep concern and solidarity with the poor, peasants and industrial workers alike that was religious in its origin, but not solely so.

Van Gogh’s deep connection to nature came from his time as a child, shy and introspective, in the rural southern Netherlands. The fields and meadows that he played in as a child were a reoccurring theme in his later artwork, and he associates them with the turning of the seasons of life and the cycles of nature.

Yet it was the stars and the night skies which entranced him the most. Carol Berry, in her book, “Vincent Van Gogh: His Spiritual Vision in Life and Art” describes his connection to the night sky like this:

“He looked to the stars in the night sky—to the “Something on High”—as a source of faith and hope, comfort and inspiration. Below his feet the fertile soil of rural Brabant nurtured the roots of his very being. His sister commented to a biographer, “Nature spoke to Vincent with a thousand voices and his soul listened.” Indeed, Vincent learned to experience life not as a set of rules, but as a series of sacred chords, individually striking his soul.”

And here is where our scripture comes in, full force! Both our reading from the book Proverbs and our Psalm, proclaim the night skies as heavenly handiwork. Just as they delight in the wonders of the natural world, so are we. Just as we are to learn about an artist, and about ourselves from her paintings, so are we called to learn about ourselves and our God from nature.

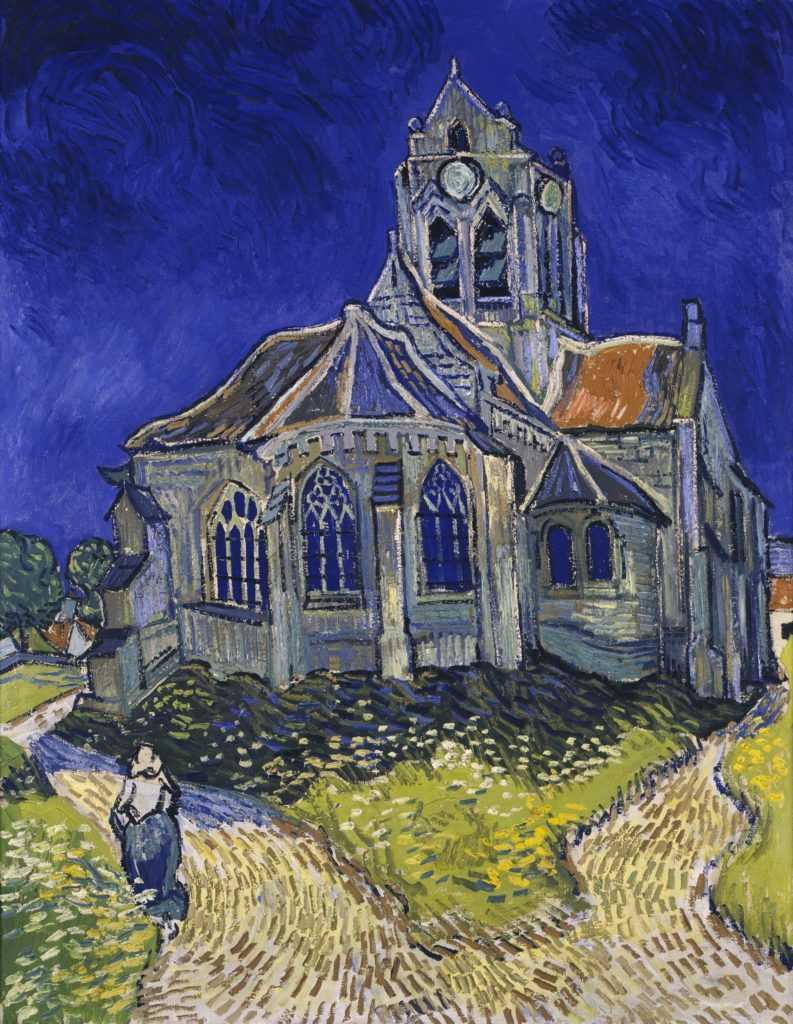

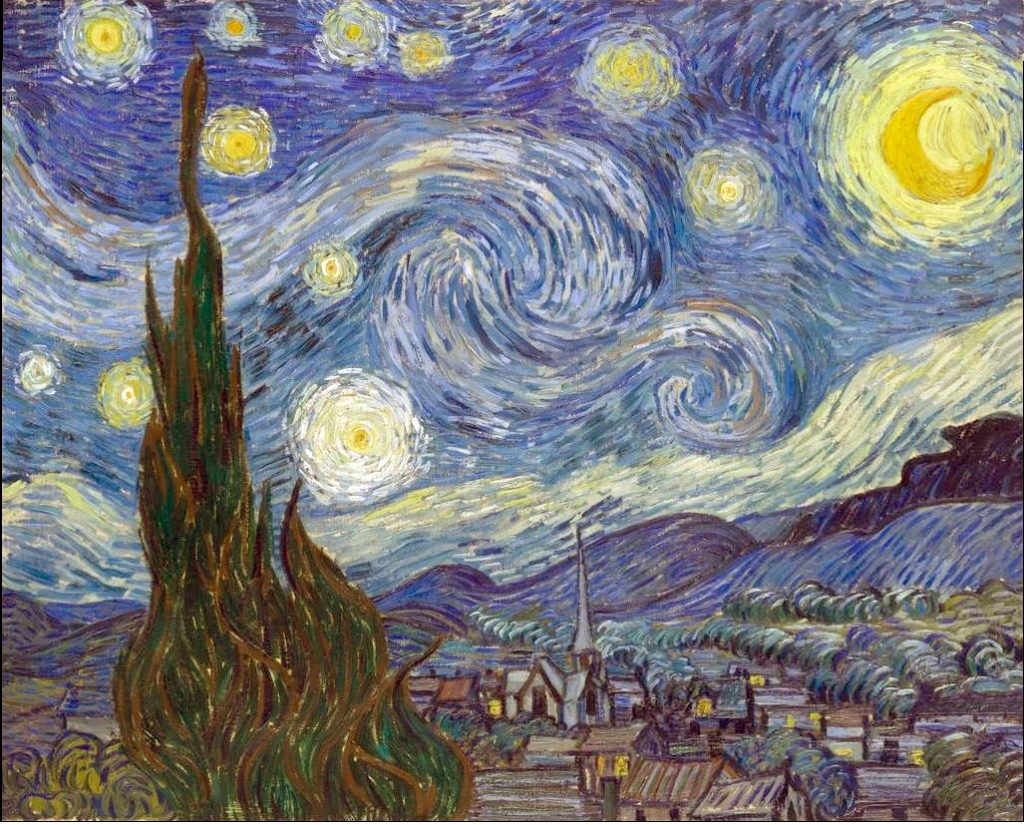

Starry Night, Van Gogh’s most famous painting, is designed to provoke this sort of awe and connection. The representation of humanity, is only in the small houses of the rural village, and are miniscule in comparison to the grandeur of the night sky. Only the church peeks up into it, and only barely so. The heavens declare the glory of God, with surreally large galaxies and stars dominating the canvas.

The heavens proclaim the glory of God.

Yet it was not only in the grandeur of nature that van Gogh found religious meaning beyond scripture.

Thankfully for us, Van Gogh was a prolific letter writer, especially to his brother Theo, and worked out a lot of his internal thoughts through writing them out. We know that he had numerous arguments with his father about if the God and Jesus Christ were knowable through writings other than the Bible.

His father argued the Orthodox position, that the Bible was the only way for people to know Jesus, and indeed God’s love.

Vincent had a broader view; he saw it in fiction, in the works of Emile Zola and George Eliot, both of whom wrote realist novels about the interactions of normal people. He believed that Christ was acting in and among the living author as much as the dead gospel writer; after all, Van Gogh reminds us in a letter, Jesus said, “Why seek ye the living among the dead?”

He also saw it in other ways too: During his time as a missionary, he wrote this in a letter to his brother Theo:

The best way of knowing God is to love many things. Love that friend, that person, that thing, whatever you will like, you will be on the right path of knowing more thoroughly afterwards; that is what I say to myself. But you have to love with a high, with a serious and intimate sympathy, with a will, with intelligence, and you must always seek to know more thoroughly, better, and more. That is what leads to God, that leads to unshakeable faith.

Vincent saw Jesus and God’s love as something that could not help but infuse all things. Like Wisdom in our reading from Proverbs, God and God’s love was here at the creation of the world and would be here at the end of it. Just as dust we were made and to dust we shall return, so too from God’s love were we made and to God’s love we shall return. If only we could love will, compassion, intelligence, and a thirst for knowledge, we would be led inevitably to God.

This leads him to find a remarkable fondness for Japanese art, culture, and philosophy, which was becoming very popular as Van Gogh was producing some of what would become his most famous work. I quote Van Gogh again:

If one studies Japanese art, then we see a man, undeniably wise and a philosopher and intelligent, who spends his time—doing what?—studying the distance from the earth to the moon?—no; studying Bismarck’s politics?—no; he studies a single blade of grass.

This is remarkably respectful for his time; let us remember that 20 years after this, the United States would ban all immigration from East Asia for decades, until the 1960s.

This is just one of many examples of his deep and abiding love and solidarity with humanity that infuses his life and work.

We heard about why he was kicked out of being a missionary- that he was too close to his congregants and thus degrading the office of pastor, but this was also in his art.

We can see it in his portraits, which are not of the wealthy and famous, but of workers, or old peasant lovers. His models did not pay him for his portraits; most of them couldn’t have afforded it if they had wanted to. Instead, Van Gogh went into the homes and fields where people were and observed them. This might have been in a dance hall, or in a café, or outside of a church. Sometimes they didn’t have to include people in them at all to tell us something beautiful about us.

The still life with Bible was painted right after his father’s death, and probably shows his father’s Bible. It’s well worn, brown on the edges. This is an old and loved Bible, opened to the prophet Isaiah, the favorite Old Testament book of many a preacher. The candles are worn low and extinguished, possibly symbolizing a life extinguished. La Joie de Vivre, a novel by Emile Zola, lies underneath it. Perhaps it represents Van Gogh in relationship to his larger than life father and the debates he had with him about life and the Gospel.

We still have much to learn about and from Van Gogh; not only to about how to appreciate the swirls of stars and galaxies in his paintings and in nature, but how each of us is, as our psalmist says, a little lower than God, a painted image of the divine artist.

I will leave us with this quote about Vincent from Carol Berry, who’s book I have quoted. I hope that one day it might apply to me as well:

Vincent learned to experience life not as a set of rules, but as a series of sacred chords, individually striking his soul.

Amen.